Topics

Category

Era

HOW POLITICS HAS SHAPED THE STATE

Politics in Minnesota

Governor Mark Dayton delivering his first State of the State address to a joint session of the Minnesota Legislature, February 9, 2011

People in Minnesota have engaged in lively politics noted for a high level of citizen participation since the founding of the state in 1858 and long before. Often, they showed a willingness to use government to improve the state’s quality of life. Though Minnesota’s political parties have at times diverged from their national counterparts, they have produced leaders who made notable contributions to the nation.

Indigenous Politics

Governing structures existed among the peoples of Mni Sota Makoce (the Dakota name from which the word Minnesota derives) well before statehood. Neither the Dakota, who occupied the southern two-thirds of Minnesota for centuries, nor the Ojibwe, who moved to the northern portion of the state from the east in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, created “national” governments. Rather, both were organized in autonomous groups of villages (called bands by Euro-Americans), each typically composed of members of five or more large kinship groups that camped, traveled, hunted, and made war together.

Decisions were made by village councils that, like the town meetings of New England, operated largely by consensus. Though many of these were limited to men, women gathered in councils of their own that also guided political decisions. The bands’ civil leaders occupied hereditary positions typically passed from father to son; their power, however, derived largely from personal influence. Other skill-specific leadership roles within bands were temporary.

Among the Ojibwe, leaders were often chosen from kinship groups deemed to have particular aptitude for medicine, religious observance, dispute resolution, and/or warfare. Leaders of related bands within a region communicated with each other and met for joint decision-making as needed. A similar loose confederation among the Iroquois—neighbors of the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes region—influenced the designers of the young United States of America in the eighteenth century.

Minnesota Becomes A State

The New Englanders who arrived in Minnesota in the mid-nineteenth century were also practitioners of highly participatory democracy. Descendants of English Puritans who had resisted rule by kings and noblemen, they governed themselves via town meetings in which all free adult males could vote and many were expected to take a turn at public office. For them, as for Native people bound by kinship ties, participating in politics was an extension of responsibility to families and enterprises.

Minnesota state government, which is modeled after the three-branch federal government, includes a two-chamber legislature whose members are elected by voters in defined geographic districts. The state’s founders opted for a large “citizen legislature” that includes the nation’s largest state senate, with sixty-seven members. At first, legislators met in regular sessions for only a few months each year; between 1879 and 1973, they met only every other year.

Settler-colonists in the new state saw government as their ally in the pursuit of prosperity. They looked to it to remove or subdue the Dakota and Ojibwe, assure access to cheap land, protect property owners’ rights, and provide transportation to link Minnesota to the rest of the nation. The first amendment to the state constitution allowed for borrowing money via “special bonds” and loaning it to four new railroad ventures. The railroad companies, however, reneged on their part of the bargain as the Panic of 1857 spread. Angry Minnesota voters passed another amendment in 1860 forbidding the use of tax money to honor the bonds. It took more than two decades and the persistence of one governor, John S. Pillsbury, for the debt to be settled.

Despite that speed bump, railroad building accelerated in the 1860s as the Civil War traumatized the nation. That war colored state politics for the remainder of the century. While Minnesota’s first governor, Henry Sibley, was a Democrat, his successor, Alexander Ramsey, and the state’s next eleven governors all affiliated with the Republican Party—the party of Lincoln. Minnesotans sided strongly with the Union, many because they hated slavery. Ramsey was the nation’s first governor to offer troops (the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment) to President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861. Minnesota’s soldiers suffered severe losses at the Battle of Gettysburg and played a major role in the Union victory at Vicksburg. Those soldiers sealed in blood a bond with the party that won the war.

Recovering From Civil War

Some of those who chose to come to Minnesota after the Civil War were newly freed enslaved people (African-Americans were granted the vote via an amendment to the state constitution in 1868). Many more were from northern Europe, with Germans making up the largest group. But those from Ireland and Scandinavia made a stronger imprint on state politics. Irish immigrants clustered in St. Paul, bringing Catholic solidarity and reliable Democratic votes to the older and, by the 1890s, smaller of the Twin Cities. Scandinavians flocked to Minneapolis and scattered to small towns and farms to the south and northwest. Their Lutheran ideas about community and government nearly matched those of earlier Yankee settlers. Republican politics, moreover, suited them. The first Norwegian-born governor of Minnesota, Republican Knute Nelson, was elected in 1892; all but five of the state’s twenty-three governors in the twentieth century possessed Scandinavian heritage.

Farmers’ zeal for the Republican Party waned as the industrial revolution advanced. As Minnesota’s timber, milling, mining, railroad and banking entrepreneurs made fortunes, a growing share of farmers felt cheated by low commodity prices and high shipping and machinery costs. Oliver H. Kelley, a farmer from Elk River, founded in 1867 the first association of farmers trying to collectively improve their lot: the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry. While the Grange (including its Minnesota branch) was apolitical, its organizational descendants were anything but. By the 1890s, the agrarian protest movement had spawned the Populist Party, whose gubernatorial candidate topped the Democrats to come in second to Nelson in 1894. Four years later, the long line of Republican governors was broken by John Lind, a Swedish-American congressman from New Ulm. He wore three party labels: Democrat, Populist, and Silver Republican.

Lind served one term and met none of his goals: higher railroad taxes, an income-based alternative to the unpopular property tax, creation of a board of control to bring accountability to state agencies and institutions, and more voter control of government through a direct primary, initiative, referendum, and recall. That agenda would endure as the Midwestern progressive movement arose in the early twentieth century.

Politics In A New Century

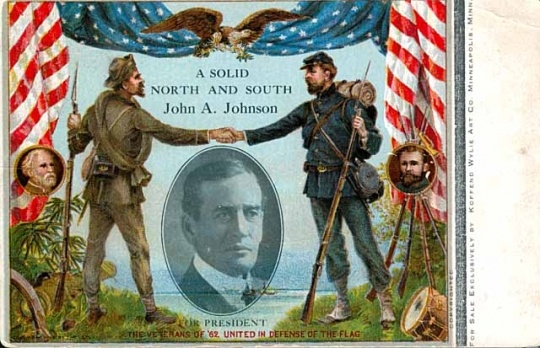

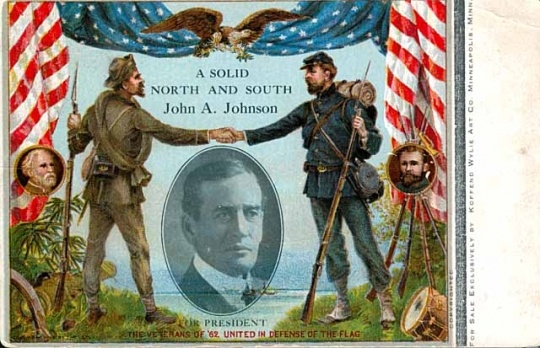

The state’s next Democratic governor, John A. Johnson, won by campaigning on progressive ideas in 1904, even as Minnesotans voted overwhelmingly for President Theodore Roosevelt, a progressive Republican. Johnson was thought to be on his way to a presidential bid when he died suddenly in September 1909. But by then, the idea that government should shield working people from the excesses of big business had caught on in the state.

Republicans dominated the state capitol in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Legislators did, however, bow to progressive calls in 1912 to ratify federal constitutional amendments authorizing an income tax and direct election of US senators. The next year, they made the legislature a nonpartisan body—a status that would endure for sixty years. Legislators caucused as Conservatives and Liberals, names that came to be nearly synonymous with Republicans and Democrats, respectively.

In 1915, state legislators allowed counties the option of banning the sale of alcohol. It was a precursor of Prohibition, which was popular with Minnesota’s Yankee and Scandinavian progressives and resisted by immigrants from Germany and Ireland. The issue also divided Minnesotans on religious lines, with Protestants favoring Prohibition and Catholics more often opposed. The US House sponsor of legislation enacting Prohibition in 1919 was Minnesota Representative Andrew Volstead, a Republican from Granite Falls.

Minnesota Republicans were less responsive to another progressive demand: votes for women. With the exception of school board elections, women did not win the right to vote in Minnesota until the US Constitution’s Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. Afterward, the Minnesota Women’s Suffrage Association evolved into the Minnesota League of Women Voters.

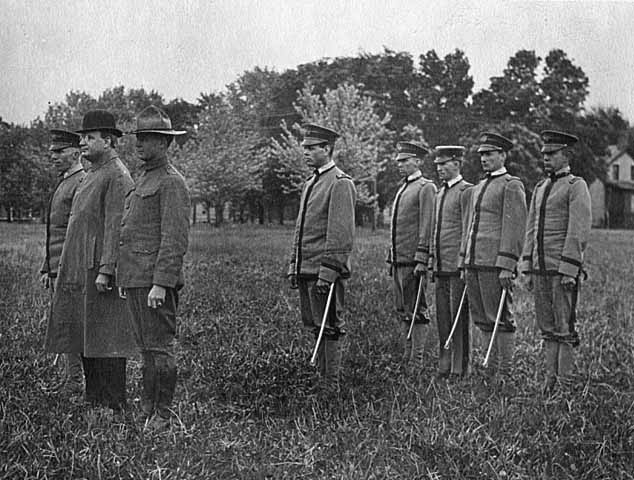

Despite the Republicans’ progressive tilt in the early twentieth century, they remained allied with big businesses. That was evident during World War I, when Governor J. A. A. Burnquist and some of the state’s largest businesses used the war as justification to surveil and forcibly silence the leaders of labor unions and the new Nonpartisan League, the latest agrarian protest movement. The harsh measures employed by the Minnesota Public Safety Commission strengthened the resolve of farmers and laborers to fight back politically. Though Burnquist won reelection in 1918, in second place was David H. Evans, who ran on a new ticket: the Farmer-Labor Party.

Rise Of The Farmer-labor Party

The new party first flexed its muscle to winning effect in a 1922 US Senate race, in which Farmer-Laborite Henrik Shipstead upset a future US secretary of state, Republican Senator Frank B. Kellogg. The next year, F-L candidate Magnus Johnson bested Republican Governor J. A. O. Preus in a special election to succeed the late US Senator Knute Nelson.

The governorship was harder for the new party to capture. But after the stock market crash in 1929, the economic distress that farmers had known in the 1920s reached urban dwellers, too, and voters turned away from the party of President Herbert Hoover. Charismatic Farmer-Laborite Floyd B. Olson took the governorship in 1930. Two years later, Farmer-Labor candidates ended Republican/Conservative control of the Minnesota House for the first time in the twentieth century.

That change led to enactment in 1933 of the state income tax, a mortgage foreclosure moratorium, and a ban on labor contracts that barred employees from joining unions. Olson sold the idea that government had a responsibility for the welfare of its citizens, and his personal appeal papered over divisions within the Farmer-Labor coalition. It was an uneasy alliance between leftists who favored state takeover of key industries and working people who simply wanted to hang on to their jobs and farms. Like Johnson before him, Olson was seen as a possible future president when death intervened. He died of stomach cancer in August 1936.

Olson’s Farmer-Labor successors failed to keep his coalition together, and by 1938, a new star was rising. Harold Stassen, a Dakota County prosecutor just thirty-one years old, sailed to an easy victory over Farmer-Labor Governor Elmer Benson. Stassen represented a shift in Republican thinking. Friendly toward organized labor and Roosevelt’s New Deal, he sought to assist those impoverished by the Depression. When war broke out again in Europe, he argued that America should not turn its back. Those ideas attracted young talent that would form the core of Minnesota’s progressive post-war Republican Party.

Stassen resigned after the 1943 legislative session and enlisted in the Navy. He became a top aide to Admiral William “Bull” Halsey and a US delegate to the conference that drafted the United Nations charter. He ran for president in 1948, leaving in Minnesota his hand-picked successors Joseph Ball and Edward Thye in the US Senate and Luther Youngdahl in the governor’s office. But Stassen came in second to Governor Thomas Dewey of New York in the Republican presidential contest. He faltered again when even Minnesota’s Republican convention delegates preferred General Dwight Eisenhower in 1952. Stassen’s party also suffered a reversal at home when Ball lost the 1948 Senate election to a newcomer, Hubert Humphrey of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party.

New Leaders Emerge

Humphrey, thirty-seven years old in 1948, had four years earlier helped engineer the merger of the fading Farmer-Labor Party and the third-place Democratic Party. Their shared support for President Franklin Roosevelt augured for union. So did Humphrey’s ambition. A Macalester College professor, Humphrey had lost the Minneapolis mayoral election in 1943. He believed a party merger would help him win in 1945, and that assessment proved correct. In 1948 Mayor Humphrey was a Senate candidate who attracted headlines with a fiery call for civil rights at the Democratic National Convention.

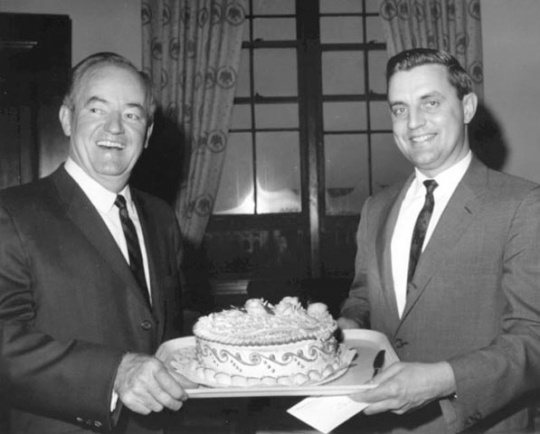

The young talent Humphrey’s first Senate campaign enlisted would lead the DFL for the next forty years. Among them were Walter Mondale, a future vice president; Orville Freeman, future governor; Arthur Naftalin and Don Fraser, future Minneapolis mayors; Arvonne Fraser, future leader of the Minnesota women’s movement; and Eugene McCarthy, a future US senator elected to the US House in 1948.

The parties that Stassen and Humphrey built were fierce competitors. But their platforms were remarkably similar in the mid-twentieth century. The center-right Minnesota Republicans and center-left DFLers both opposed racial bias in housing and employment. Both supported public assistance for the disabled. Both were willing to use state tax revenue to boost funding for schools and local governments, so that the quality of education and municipal services was not dependent on a community’s property wealth. Both sought to safeguard the natural environment. Republican governors Luther Youngdahl, Elmer L. Andersen, Harold LeVander, Al Quie, and Arne Carlson embraced those positions. So did DFL governors Orville Freeman, Karl Rolvaag, Wendell Anderson, and Rudy Perpich.

At mid-century, both Minnesota parties stood to the philosophical left of their national counterparts. When Republicans chose conservative Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater for president in 1964, a majority of Minnesota’s national convention delegates cast a protest vote for former US Representative Walter Judd of Minneapolis. A decade later, the Minnesota GOP renamed itself the Independent-Republican Party to distance itself from the Watergate-stained national party. The name would stick until 1995.

Minnesotan Politicians On The National Stage

Humphrey gained fame throughout the 1950s as a leading voice for labor and civil rights. In 1960, he lost the Democratic presidential nomination to a more moderate-minded candidate, John F. Kennedy. Humphrey’s Senate sponsorship of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was followed by his selection as President Lyndon Johnson’s running mate. When Johnson opted not to seek reelection in 1968 at the height of the Vietnam War, Vice President Humphrey ran again for president. This time, he was the establishment candidate, facing anti-war challenges from his fellow Minnesotan Senator Eugene McCarthy and, until his assassination on June 5, New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

The Humphrey-McCarthy split was keenly felt in the DFL. Only two years earlier, it had endured a gubernatorial primary battle between Governor Karl Rolvaag and Lieutenant Governor Alexander M. “Sandy” Keith. Both times, intraparty conflict benefitted the opposite party. Harold LeVander beat Rolvaag, who had won the DFL primary despite the party’s endorsement of Keith. Humphrey lost the presidential election to Richard Nixon, though he carried Minnesota by 200,000 votes. By an even larger margin, Minnesotans returned Humphrey to the US Senate in 1970. He remained in office until his death in January 1978, long enough to see his protégé, Mondale, elected vice president in 1976.

Between 1911 and 1966, the legislature did little to adjust congressional and legislative maps to equalize district population. That neglect allowed rural Minnesotans to gain advantage as the Twin Cities population grew. Redistricting was finally done under federal court order in time for the 1966 election and would follow every census thereafter. More Twin Cities legislative seats resulted and helped DFLers win control of the full legislature and governorship in 1973—a first for the party. A host of changes in policy and lawmaking processes ensued, led by Senate Majority Leader Nicholas Coleman and House Speaker Martin Olav Sabo. The legislature began meeting every year. Its members again took party labels, and meetings were opened to the public. A nation-leading system of public campaign financing was created.

At the same time, women arrived at the legislature in bigger numbers. Only one woman, Helen McMillan, served in the legislature in 1971‒72; a decade later, the total was twenty-four. (As of 2019, the share of women in the body has exceeded 25 percent since 1993. The state’s first female US senator, Democrat Amy Klobuchar, was elected in 2006.)

The 1974 and 1976 elections that followed Watergate brought DFLers their largest majorities in state history. But Republicans rebounded in 1978 when voters rejected DFL Governor Wendell Anderson’s self-appointment to the US Senate in late 1976 after Mondale became vice president. Republicans Rudy Boschwitz and Dave Durenberger won US Senate seats, and Al Quie ousted the former lieutenant governor who succeeded Anderson: Hibbing dentist Rudy Perpich.

Perpich returned to office in 1982 after several years of state budget turmoil led Quie not to run again. Perpich’s theme was that Minnesota could compete in the global economy as “the Brainpower State,” home to a well-educated workforce. Perpich served eight more years for a ten-year total, the longest of any Minnesota governor.

Minnesota gave Mondale his only state win in his 1984 presidential bid as President Ronald Reagan scored a landslide victory. Reagan’s influence, however, was pushing the Independent-Republican Party to the ideological right. So were the former DFLers and conservative Christians who were attracted to the I-R Party by its platform’s opposition to legal abortion. Businesses that sought lower taxes and less regulation also stepped up their activity on Republicans’ behalf in Minnesota and around the country in the 1980s.

Power Shifts And Competition

Conservatives were in charge at Independent-Republican conventions by 1990, when businessman Jon Grunseth was endorsed to challenge Perpich. But revelations about sexual misconduct led Grunseth to leave the contest nine days before the election. His spot on the ballot went to State Auditor Arne Carlson, a GOP moderate who had run well behind Grunseth in the primary. Carlson went on to two terms as governor. Then, in 1998, former professional wrestler Jesse Ventura became the first third-party governor in the state since the 1930s. It was not until Tim Pawlenty was elected governor in 2002 that the conservative shift of the Republican Party was fully felt at the statehouse.

Perpich’s 1990 defeat coincided with the election of Carleton College professor Paul Wellstone to the US Senate. An energetic orator and decided liberal, Wellstone solidified DFL dominance in the Twin Cities. His vote against authorizing a unilateral American attack on Iraq in 2002 was the only such vote cast by a Democrat facing a serious reelection challenge that year. His standing in the polls against his Republican challenger, former St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman, rose in the days after the vote. Then tragedy struck: Wellstone, his wife, their daughter, and several aides were killed in a plane crash twelve days before the election. Coleman won the seat, but six years later he lost it to former entertainer Al Franken in the closest US Senate race in state history. Franken’s victory margin was 312 votes.

Though Minnesota has been Democratic “blue” in every presidential election save one (1972) since 1960, state politics have been highly competitive. But a wide philosophical gap has separated the two parties in the twenty-first century. A geographic split—DFL hegemony in the Twin Cities, Republican dominion in Greater Minnesota—has added to the parties’ difficulty in reaching consensus on state policy. In 1973, Time magazine described Minnesota as “The state that works.” State government shutdowns in 2005 and 2011 and recurring lawmaking gridlock in the 2010s have called that reputation into question.

Bibliography

Atkins, Annette. Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Berg, Tom. Minnesota’s Miracle: Lessons from a Government That Worked. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Bergman, Klas. Scandinavians in the State House: How Nordic Immigrants Shaped Minnesota Politics. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

Blegen, Theodore C. Minnesota: A History of the State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1963. Second edition 1975.

Carley, Kenneth. Minnesota in the Civil War: An Illustrated History. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000.

Durenberger, Dave, with Lori Sturdevant. When Republicans Were Progressive. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018.

Elazar, Daniel J., Virginia Gray, and Wyman Spano. Minnesota Politics and Government. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vols. I‒IV. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1921. Revised edition 1956.

Gagnon, Gregory O. Culture and Customs of the Sioux Indians. Part of the series “Culture and Customs of Native People in America.” Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011.

Gieske, Millard L., and Steven J. Keillor. Norwegian Yankee: Knute Nelson and the Failure of American Politics. Northfield, MN: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1995.

Gilman, Rhoda R. Stand Up! The Story of Minnesota’s Protest Tradition. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Haynes, John Earl. Dubious Alliance: The Making of Minnesota’s DFL Party. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Holmquist, June Drenning, ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1981.

Lass, William E. Minnesota: A History. Second edition. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

Lebedoff, David. The Twenty-First Ballot: A Political Party Struggle in Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1969.

Lofy, Bill. Paul Wellstone: The Life of a Passionate Progressive. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Milton, John Watson. For the Good of the Order: Nick Coleman and the High Tide of Liberal Politics in Minnesota, 1971‒1981. St. Paul: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2012.

Mitau, G. Theodore. Politics in Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1960. Revised edition 1970.

Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Historical information.

https://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/historical

Peacock, Thomas, and Marlene Wisuri. Ojibwe: We Look in All Directions. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2002.

Solberg, Carl. Hubert Humphrey, A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton, 1984.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Werle, Steve. Stassen Again. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015.

Wills, Jocelyn. Boosters, Hustlers and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849‒1883. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005.

Related Resources

Primary

Wendell R. Anderson papers, 1930–2004

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00476.xml

Description: Senatorial files, correspondence, legislative files and bills, and other miscellaneous materials

Wendell R. Anderson subject files, 1971–1976

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00587.xml

Description: Correspondence, reports, legislation, print and near-print items, and other materials covering a wide variety of topics relating to public policy issues, Governor's Office administration, state agencies, legislation, and budget. Specific topics covered include taxes, crime and prison reform, education, and agriculture.

Rudy Boschwitz papers, 1953–1993

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00013.xml

Description: Senatorial records of Republican Rudy Boschwitz, who served two terms in the US Senate, from 1979 to 1991.

J. A. A. Burnquist papers, 1884–1961

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers documenting Republican politician Burnquist's career as St. Paul lawyer, state representative, lieutenant governor, governor, state attorney general, and relating to his years of retirement.

Records of Governor J. A. A. Burnquist, (1915–1927 (bulk 1915–1921)

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gov033.xml

Description: General correspondence, telegrams, subject files on public policy matters, files on state departments and agencies, organizations files, and materials relating to pardons and tax-forfeited property.

David Durenberger senatorial files, 1954–1996

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00257.pdf

Description: Papers of a three-term Republican US Senator from Minnesota who served from 1978 to 1995.

Arvonne S. Fraser papers, 1947–2008

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00034.xml

Description: Correspondence, schedules, speech files, draft and published writings, extensive background and conference files, audio and video recordings, and administrative and programmatic files related to Fraser's involvement with women's organizations, Democratic party politics, government agencies, and educational institutions, both in Minnesota and nationally.

Orville Freeman papers, ca. 1903–1919, 1941–2003

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00372.xml

Description: Correspondence and other papers of a Minneapolis attorney who served as a Democratic-Farmer-Labor governor of Minnesota and US Secretary of Agriculture.

Orville Freeman departmental and general files, 1955–1960

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00062.xml

Description: General correspondence, state department and agency files, federal department files, parole correspondence, Minnesota organizations files, and subject files, including considerable political, public policy, and campaign materials.

Hubert H. Humphrey papers, ca. 1883–1982

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00720.xml

Description: Files detailing the life and career of Humphrey, including his service as mayor of Minneapolis, his first term as a US senator from Minnesota, service as vice president of the United States, and materials pertaining to his personal life and 1968 and 1970 senate campaigns.

Frank B. Kellogg papers, 1884–1962

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00982.xml

Description: Correspondence, memoranda, speeches, background materials, news clippings, and other papers of a Republican Senator from Minnesota, ambassador to Great Britain, secretary of state, Nobel Peace Prize recipient, and judge on the Permanent court of International Justice (World Court) who, with French foreign minister Aristide Briand, authored the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.

Coya Knutson papers, 1905‒1999

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Congressional files and biographical materials documenting Minnesota's first female member of Congress (Democratic-Farmer-Labor, 1955‒1958).

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00246.xml

Walter Mondale papers, 1900–2008

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00697.xml

Description: Senatorial, vice presidential, ambassadorial, political papers and campaign files, and personal papers of a US senator from Minnesota, vice president of the United States, ambassador to Japan, and special envoy to Indonesia.

Attorney General Walter Mondale subject files (series 2), 1955–1965

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/ag0016.pdf

Description: Subject files compiled and used by the attorney general's office under Walter Mondale, relating to a wide variety of subjects and issues of interest to the office staff. They include some Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party campaign and political matters, including Mondale's campaign opponents. Some of the files were created by Mondale's predecessor, Miles Lord.

Knute Nelson papers, 1861–1924

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00578.xml

Description: Correspondence and miscellany documenting Nelson's career as a soldier, a country lawyer and politician, as governor of Minnesota, and particularly as United States senator. The majority of the papers focus on political and legislative affairs, either in Minnesota or reflecting Minnesota interests.

Records of Floyd B. Olson, Hjalmar Petersen, and Elmer A. Benson, 1932–1938

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00063.xml

Description: General correspondence, subject matter files, state department files, federal department files, and organization files documenting the gubernatorial service of Olson (1931–1936), Petersen (1936–1937), and Benson (1937–1939).

Records of Governor John S. Pillsbury, 1875–1891

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00626.xml

Description: Assorted files on public policy matters, including materials relating to public lands, railroads, grasshopper relief, seed grain, pardons, and applications for and appointments to office.

Alexander Ramsey and family personal papers and governor's records, 1829–1965

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/m0203.pdf

Description: Microfilmed correspondence, diaries, scrapbooks, and other materials documenting the career and family of Alexander Ramsey.

Records of Governor Alexander Ramsey, 1860–1863

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gov016.xml

Description: Accounting records, records concerning both civil and military appointments, letters received, records relating to pardons and other criminal matters, and petitions.

Henrik Shipstead papers, 1913–1953

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence, speeches, scrapbooks, clippings, news releases, printed items, and related materials concerning Shipstead's career as US senator from Minnesota, first as a member of the Farmer-Labor party and then as a Republican.

Henry H. Sibley papers, 1815–1932

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00595.xml

Description: Correspondence, financial records, legal papers, speeches, research note cards, and miscellany of Sibley, an early Minnesota fur trader, entrepreneur, and governor.

Harold Stassen papers, 1910s–1999

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00202.xml

Description: Papers documenting the life and career of a former Minnesota governor, presidential contender, naval officer, United Nations charter delegate, and Eisenhower cabinet member.

Rosalie Wahl papers, 1958–1998

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00430.xml

Description: Personal papers from the judicial chambers of Rosalie Wahl, first woman appointed (1977) and successively elected (1978, 1984, 1990) to the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Paul David Wellstone campaign records, 1962–2002

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/01138.xml

Description: Issue files, news clippings, audio and video cassettes, photographs, and other campaign records of three election campaigns waged by Wellstone, a progressive Democrat who represented Minnesota in the US Senate from 1991 to 2002.

Secondary

Adams, John S., and Barbara J. VanDrasek. Minneapolis-St. Paul: People, Places and Public Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Andersen, Elmer L. A Man’s Reach: The Autobiography of Elmer L. Andersen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Davis, W. Harry. Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2003.

Esbjornson, Robert. A Christian in Politics: Luther W. Youngdahl. Minneapolis: T. S. Denison, 1955.

Fraser, Arvonne. She’s No Lady. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2007.

Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Johnson, Cecil M. Minnesota’s Ole O. Sageng, 1871‒1963. Fergus Falls, MN: Otter Tail County Historical Society, 2015.

Latz, Robert (Bob). Jews in Minnesota Politics: The Inside Stories. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2007.

Mayer, George H. The Political Career of Floyd B. Olson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951.

Millikan, William. A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903‒1947. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

Sturdevant, Lori, with George S. Pillsbury. The Pillsburys of Minnesota. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2011.

Swain, Thomas H., with Lori Sturdevant. Citizen Swain: Tales of a Minnesota Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Wingerd, Mary Lethert. Claiming the City: Politics, Faith and the Power of Place in St. Paul. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Web

Governor of Minnesota.

https://mn.gov/governor

Minnesota State Legislature.

https://www.leg.state.mn.us

Minnesota Supreme Court.

http://www.mncourts.gov/SupremeCourt.aspx

Related Images

Minnesota Supreme Court justices, 2018. Pictured are (front row, left to right): Justice G. Barry Anderson, Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea, and Justice David L. Lillehaug, as well as (back row, left to right: Justice Anne K. McKeig, Justice Natalie E. Hudson, Justice Margaret H. Chutich, and Justice Paul C. Thissen.

.jpg)

Ilhan Omar

Ilhan Omar’s official portrait for the 116th US Congress, December 3, 2018. Photograph by Kristie Boyd, US House Office of Photography. Public domain.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

Governor Mark Dayton delivering an address to state legislators

Governor Mark Dayton delivering his first State of the State address to a joint session of the Minnesota Legislature, February 9, 2011

Holding Location

Articles

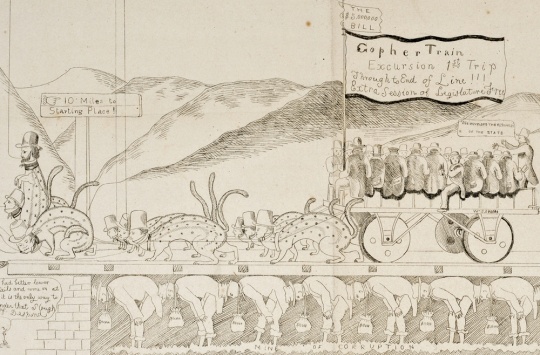

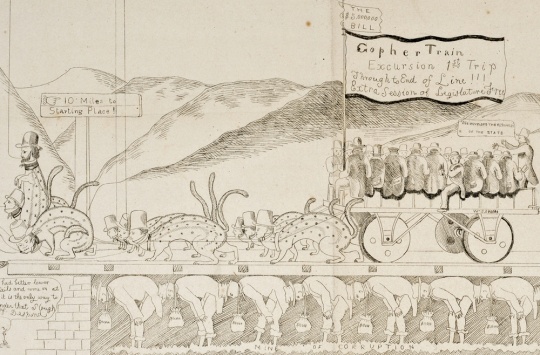

"Gopher Train" illustration

"Gopher Train" illustration by Robert O. Sweeny made in opposition to a proposed amendment to the Minnesota State Constitution allowing the state to issue $5,000,0000 worth of bonds to assist railroad construction, 1857.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

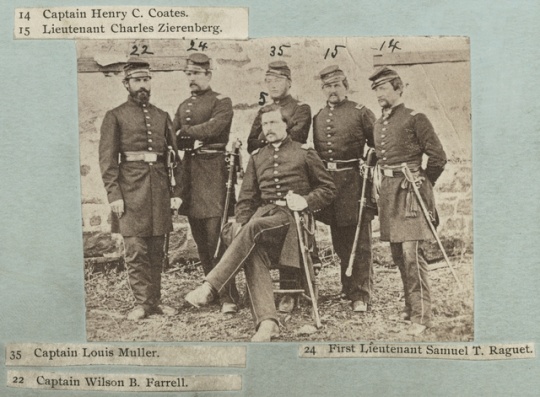

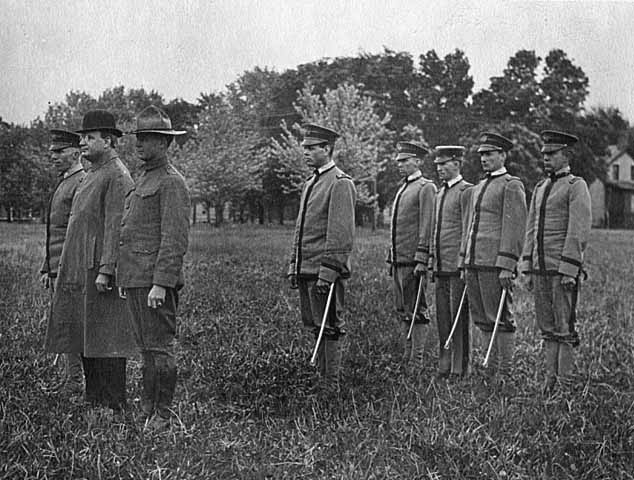

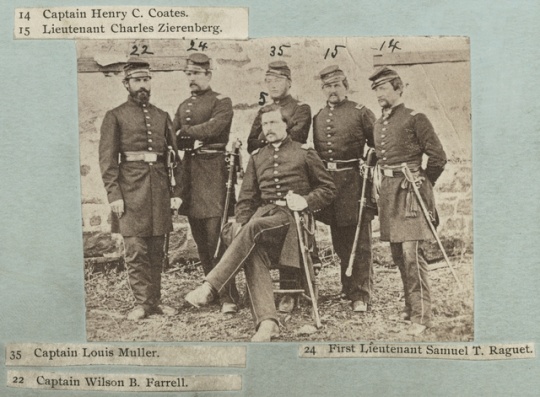

Civil War officers

Civil War officers Henry C. Coates, Mark W. Downie, Wilson B. Farrell, Louis Muller, Samuel T. Raguet, and Charles Zierenberg, ca. 1862.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

RNC delegate ribbon,1892

Republican National Convention delegate’s ribbon, 1892.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

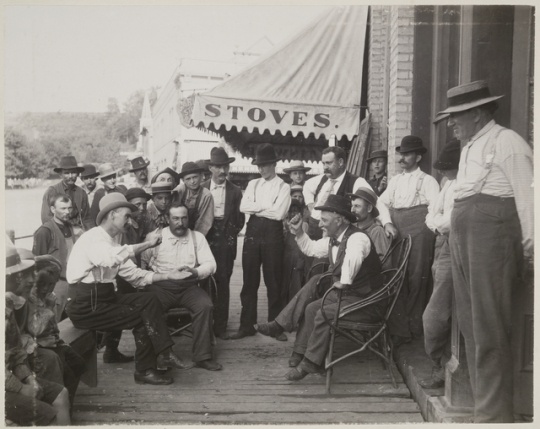

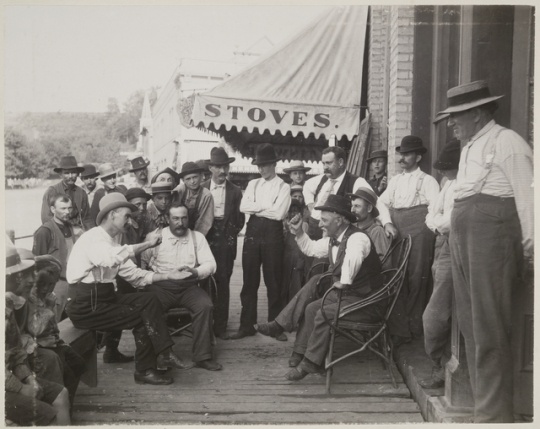

Jordanians discussing politics, 1895

Men in front of C.H. Casey Hardware store in Jordan discussing politics, ca. 1895.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

John Johnson campaign poster, 1908

Political postcard for John A. Johnson (Governor of Minnesota) for President, 1908.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Political Equality Club, Minneapolis

Political Equality Club, Minneapolis, ca. 1915. Photo by Fred. W. Bates.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Burnquist and troops, 1916

Governor J. A. A. Burnquist with military group, ca. 1916.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Floyd Olson delivering speech, 1932

Governor Floyd B. Olson, ca. 1932. Photo by St. Paul Daily News

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Harold Stassen

Harold Stassen, ca. 1937.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

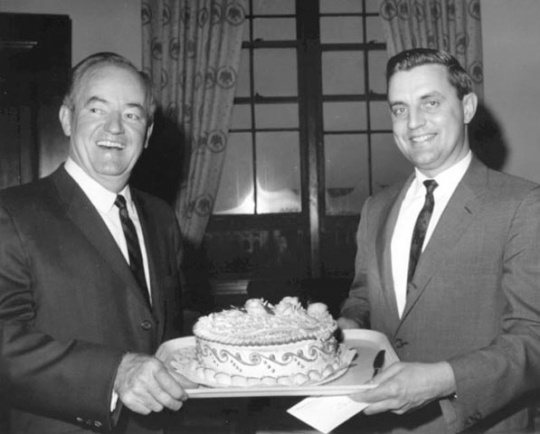

Walter Mondale and Hubert Humphrey, 1967

Hubert H. Humphrey with Walter Mondale at a surprise party celebrating Mondale's thirty-ninth birthday, 1967.

Holding Location

More Information

Coya Knutson on the campaign trail

Coya Knutson connects with a voter during her congressional reelection campaign, ca. 1955.

Holding Location

More Information

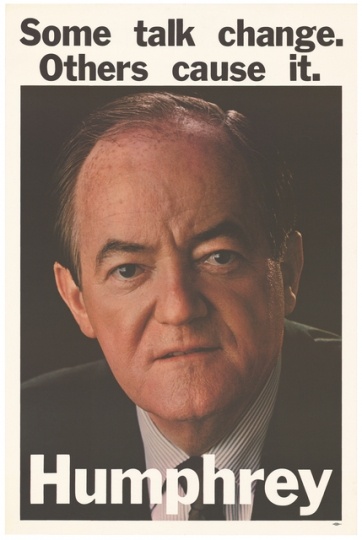

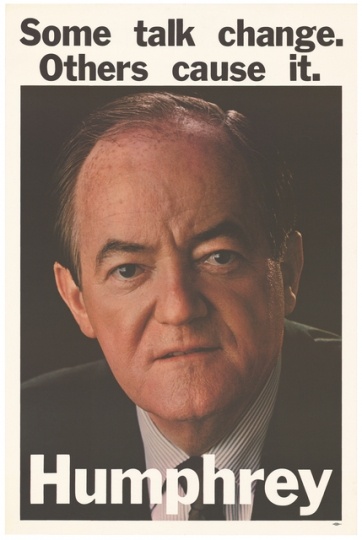

Humphrey Campaign Poster, 1968

Hubert H. Humphrey campaign poster: "Some talk change. Others cause it," 1968.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

"McCarthy for President" button

"McCarthy for President" button, 1968.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Minnesota Senate opening, 1983

Senate members take the oath of office at the opening of the session, 1983. Photo by Mark M. Nelson.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

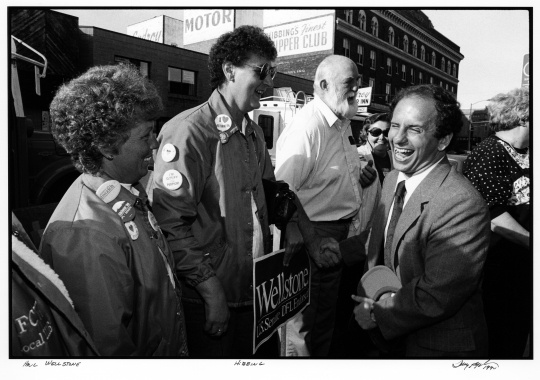

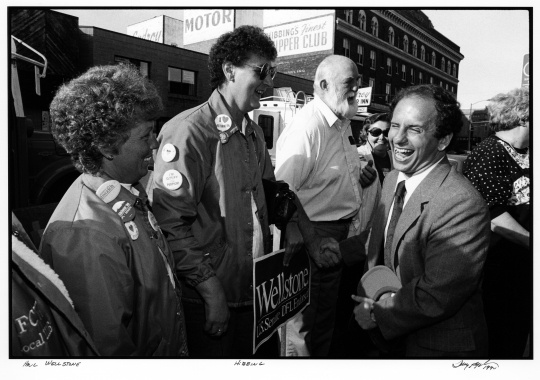

Paul Wellstone

Paul Wellstone in Hibbing, Minnesota, 1990. Photo by Terry Gydesen. Used with the permission of Terry Gydesen.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

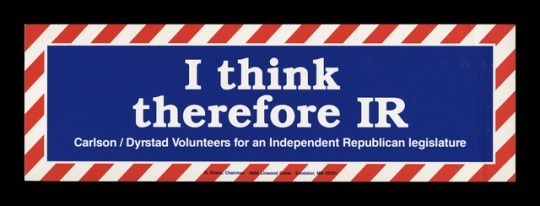

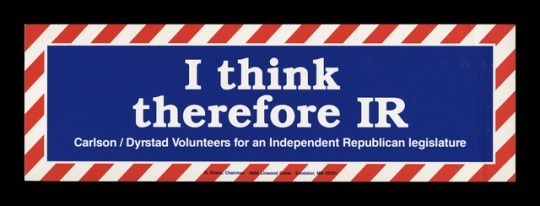

Gubernatorial campaign bumper sticker, 1990.

Gubernatorial campaign bumper sticker for Independent Republican ticket for Arne Carlson and Joanell Dyrstad, 1990.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Mee Moua

State Senator Mee Moua, ca. 2003. Minnesota Senate Photographer's Office.

Public domain

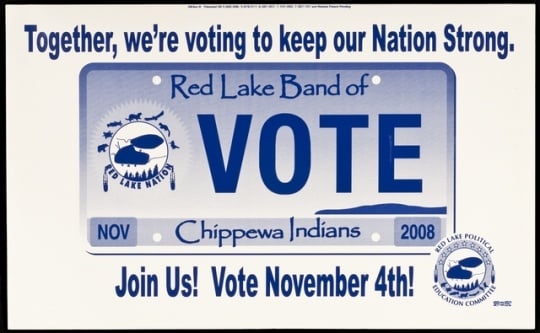

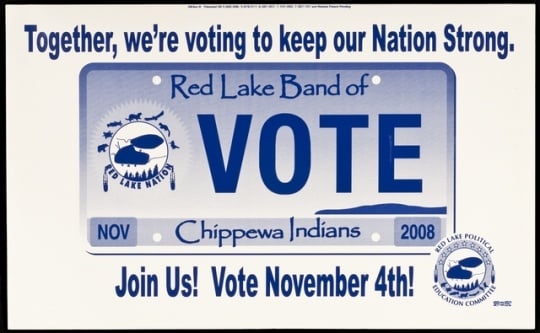

Red Lake political yard sign

Red Lake Band of Ojibwe political yard sign, ca. 2008.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Minnesota Supreme Court justices

Minnesota Supreme Court justices, 2018. Pictured are (front row, left to right): Justice G. Barry Anderson, Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea, and Justice David L. Lillehaug, as well as (back row, left to right: Justice Anne K. McKeig, Justice Natalie E. Hudson, Justice Margaret H. Chutich, and Justice Paul C. Thissen.

Articles

More Information

.jpg)

Ilhan Omar

Ilhan Omar’s official portrait for the 116th US Congress, December 3, 2018. Photograph by Kristie Boyd, US House Office of Photography. Public domain.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

Governor Mark Dayton delivering an address to state legislators

Governor Mark Dayton delivering his first State of the State address to a joint session of the Minnesota Legislature, February 9, 2011

Holding Location

Articles

"Gopher Train" illustration

"Gopher Train" illustration by Robert O. Sweeny made in opposition to a proposed amendment to the Minnesota State Constitution allowing the state to issue $5,000,0000 worth of bonds to assist railroad construction, 1857.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Civil War officers

Civil War officers Henry C. Coates, Mark W. Downie, Wilson B. Farrell, Louis Muller, Samuel T. Raguet, and Charles Zierenberg, ca. 1862.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

RNC delegate ribbon,1892

Republican National Convention delegate’s ribbon, 1892.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Jordanians discussing politics, 1895

Men in front of C.H. Casey Hardware store in Jordan discussing politics, ca. 1895.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

John Johnson campaign poster, 1908

Political postcard for John A. Johnson (Governor of Minnesota) for President, 1908.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Political Equality Club, Minneapolis

Political Equality Club, Minneapolis, ca. 1915. Photo by Fred. W. Bates.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Burnquist and troops, 1916

Governor J. A. A. Burnquist with military group, ca. 1916.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Floyd Olson delivering speech, 1932

Governor Floyd B. Olson, ca. 1932. Photo by St. Paul Daily News

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Harold Stassen

Harold Stassen, ca. 1937.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Walter Mondale and Hubert Humphrey, 1967

Hubert H. Humphrey with Walter Mondale at a surprise party celebrating Mondale's thirty-ninth birthday, 1967.

Holding Location

More Information

Coya Knutson on the campaign trail

Coya Knutson connects with a voter during her congressional reelection campaign, ca. 1955.

Holding Location

More Information

Humphrey Campaign Poster, 1968

Hubert H. Humphrey campaign poster: "Some talk change. Others cause it," 1968.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

"McCarthy for President" button

"McCarthy for President" button, 1968.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

More Information

Minnesota Senate opening, 1983

Senate members take the oath of office at the opening of the session, 1983. Photo by Mark M. Nelson.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Paul Wellstone

Paul Wellstone in Hibbing, Minnesota, 1990. Photo by Terry Gydesen. Used with the permission of Terry Gydesen.

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Gubernatorial campaign bumper sticker, 1990.

Gubernatorial campaign bumper sticker for Independent Republican ticket for Arne Carlson and Joanell Dyrstad, 1990.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

Mee Moua

State Senator Mee Moua, ca. 2003. Minnesota Senate Photographer's Office.

Public domain

Red Lake political yard sign

Red Lake Band of Ojibwe political yard sign, ca. 2008.

All rights reserved

Holding Location

Articles

More Information

Minnesota Supreme Court justices

Minnesota Supreme Court justices, 2018. Pictured are (front row, left to right): Justice G. Barry Anderson, Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea, and Justice David L. Lillehaug, as well as (back row, left to right: Justice Anne K. McKeig, Justice Natalie E. Hudson, Justice Margaret H. Chutich, and Justice Paul C. Thissen.

Articles

More Information

.jpg)

Ilhan Omar

Ilhan Omar’s official portrait for the 116th US Congress, December 3, 2018. Photograph by Kristie Boyd, US House Office of Photography. Public domain.

Public domain

Holding Location

Articles

Related Articles

Overview

Minnesota’s political heritage springs from consensus-based Dakota and Ojibwe council systems as well as New England’s Puritans, who rejected royalist rule in favor of broadly participatory democracy.

The Civil War made an enduring imprint on Minnesota politics by building a lasting affinity between pro-Union citizens, including veterans, and the Republican Party.

Scandinavian and, to a lesser extent, Irish migration to Minnesota in the two decades after the Civil War brought people imbued with a strong culture of civic participation that meshed well with the politics of earlier settler-colonists.

Farmers’ complaints about economic servitude at the hands of wealthy Twin Cities milling and railroad interests developed into populist political stirrings that, in the late 1890s, broke Republicans’ forty-year lock on state politics.

Prohibition divided Catholics and Protestants, who established distinct political loyalties.

Harsh measures employed by the pro-business Minnesota Public Safety Commission during World War I fueled a backlash that spurred the creation of the Farmer‒Labor Party in 1918.

The Farmer-Labor Party’s heyday during the worst years of the Great Depression led to the establishment of the state income tax.

Republican Governor Harold Stassen, elected in 1938, gave his state party a progressive and internationalist identity that would endure for the next forty years.

A 1944 merger of two parties created the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. Its first winning US Senate candidate, Hubert Humphrey in 1948, would achieve national prominence as an advocate for civil rights.

Legislative redistricting—avoided for more than fifty years—finally occurred in 1966, bringing urban issues to the fore and helping DFLers take control of the state senate in 1972 for the first time since statehood.

Minnesotans Harold Stassen, Hubert Humphrey, and Walter Mondale competed unsuccessfully for the presidency.

The rift between two Minnesota Democratic presidential candidates, Hubert Humphrey and Eugene McCarthy, over US involvement in the Vietnam War contributed to the election of Republican Richard Nixon in 1968.

Propelled by the abortion issue and stepped-up business political activism, the Minnesota Republican Party moved to the right in the 1980s and 1990s.

Chronology

1858

1861

1898

1917

1922

1932

1938

1944

1954

1954

1968

1972

1978

1990

2002

2016

Bibliography

Atkins, Annette. Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Berg, Tom. Minnesota’s Miracle: Lessons from a Government That Worked. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Bergman, Klas. Scandinavians in the State House: How Nordic Immigrants Shaped Minnesota Politics. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

Blegen, Theodore C. Minnesota: A History of the State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1963. Second edition 1975.

Carley, Kenneth. Minnesota in the Civil War: An Illustrated History. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000.

Durenberger, Dave, with Lori Sturdevant. When Republicans Were Progressive. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018.

Elazar, Daniel J., Virginia Gray, and Wyman Spano. Minnesota Politics and Government. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vols. I‒IV. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1921. Revised edition 1956.

Gagnon, Gregory O. Culture and Customs of the Sioux Indians. Part of the series “Culture and Customs of Native People in America.” Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011.

Gieske, Millard L., and Steven J. Keillor. Norwegian Yankee: Knute Nelson and the Failure of American Politics. Northfield, MN: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1995.

Gilman, Rhoda R. Stand Up! The Story of Minnesota’s Protest Tradition. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Haynes, John Earl. Dubious Alliance: The Making of Minnesota’s DFL Party. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Holmquist, June Drenning, ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1981.

Lass, William E. Minnesota: A History. Second edition. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

Lebedoff, David. The Twenty-First Ballot: A Political Party Struggle in Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1969.

Lofy, Bill. Paul Wellstone: The Life of a Passionate Progressive. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Milton, John Watson. For the Good of the Order: Nick Coleman and the High Tide of Liberal Politics in Minnesota, 1971‒1981. St. Paul: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2012.

Mitau, G. Theodore. Politics in Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1960. Revised edition 1970.

Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Historical information.

https://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/historical

Peacock, Thomas, and Marlene Wisuri. Ojibwe: We Look in All Directions. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2002.

Solberg, Carl. Hubert Humphrey, A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton, 1984.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Werle, Steve. Stassen Again. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015.

Wills, Jocelyn. Boosters, Hustlers and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849‒1883. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005.

Related Resources

Primary

Wendell R. Anderson papers, 1930–2004

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00476.xml

Description: Senatorial files, correspondence, legislative files and bills, and other miscellaneous materials

Wendell R. Anderson subject files, 1971–1976

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00587.xml

Description: Correspondence, reports, legislation, print and near-print items, and other materials covering a wide variety of topics relating to public policy issues, Governor's Office administration, state agencies, legislation, and budget. Specific topics covered include taxes, crime and prison reform, education, and agriculture.

Rudy Boschwitz papers, 1953–1993

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00013.xml

Description: Senatorial records of Republican Rudy Boschwitz, who served two terms in the US Senate, from 1979 to 1991.

J. A. A. Burnquist papers, 1884–1961

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers documenting Republican politician Burnquist's career as St. Paul lawyer, state representative, lieutenant governor, governor, state attorney general, and relating to his years of retirement.

Records of Governor J. A. A. Burnquist, (1915–1927 (bulk 1915–1921)

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gov033.xml

Description: General correspondence, telegrams, subject files on public policy matters, files on state departments and agencies, organizations files, and materials relating to pardons and tax-forfeited property.

David Durenberger senatorial files, 1954–1996

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00257.pdf

Description: Papers of a three-term Republican US Senator from Minnesota who served from 1978 to 1995.

Arvonne S. Fraser papers, 1947–2008

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00034.xml

Description: Correspondence, schedules, speech files, draft and published writings, extensive background and conference files, audio and video recordings, and administrative and programmatic files related to Fraser's involvement with women's organizations, Democratic party politics, government agencies, and educational institutions, both in Minnesota and nationally.

Orville Freeman papers, ca. 1903–1919, 1941–2003

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00372.xml

Description: Correspondence and other papers of a Minneapolis attorney who served as a Democratic-Farmer-Labor governor of Minnesota and US Secretary of Agriculture.

Orville Freeman departmental and general files, 1955–1960

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00062.xml

Description: General correspondence, state department and agency files, federal department files, parole correspondence, Minnesota organizations files, and subject files, including considerable political, public policy, and campaign materials.

Hubert H. Humphrey papers, ca. 1883–1982

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00720.xml

Description: Files detailing the life and career of Humphrey, including his service as mayor of Minneapolis, his first term as a US senator from Minnesota, service as vice president of the United States, and materials pertaining to his personal life and 1968 and 1970 senate campaigns.

Frank B. Kellogg papers, 1884–1962

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00982.xml

Description: Correspondence, memoranda, speeches, background materials, news clippings, and other papers of a Republican Senator from Minnesota, ambassador to Great Britain, secretary of state, Nobel Peace Prize recipient, and judge on the Permanent court of International Justice (World Court) who, with French foreign minister Aristide Briand, authored the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.

Coya Knutson papers, 1905‒1999

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Congressional files and biographical materials documenting Minnesota's first female member of Congress (Democratic-Farmer-Labor, 1955‒1958).

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00246.xml

Walter Mondale papers, 1900–2008

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00697.xml

Description: Senatorial, vice presidential, ambassadorial, political papers and campaign files, and personal papers of a US senator from Minnesota, vice president of the United States, ambassador to Japan, and special envoy to Indonesia.

Attorney General Walter Mondale subject files (series 2), 1955–1965

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/ag0016.pdf

Description: Subject files compiled and used by the attorney general's office under Walter Mondale, relating to a wide variety of subjects and issues of interest to the office staff. They include some Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party campaign and political matters, including Mondale's campaign opponents. Some of the files were created by Mondale's predecessor, Miles Lord.

Knute Nelson papers, 1861–1924

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00578.xml

Description: Correspondence and miscellany documenting Nelson's career as a soldier, a country lawyer and politician, as governor of Minnesota, and particularly as United States senator. The majority of the papers focus on political and legislative affairs, either in Minnesota or reflecting Minnesota interests.

Records of Floyd B. Olson, Hjalmar Petersen, and Elmer A. Benson, 1932–1938

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00063.xml

Description: General correspondence, subject matter files, state department files, federal department files, and organization files documenting the gubernatorial service of Olson (1931–1936), Petersen (1936–1937), and Benson (1937–1939).

Records of Governor John S. Pillsbury, 1875–1891

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gr00626.xml

Description: Assorted files on public policy matters, including materials relating to public lands, railroads, grasshopper relief, seed grain, pardons, and applications for and appointments to office.

Alexander Ramsey and family personal papers and governor's records, 1829–1965

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/m0203.pdf

Description: Microfilmed correspondence, diaries, scrapbooks, and other materials documenting the career and family of Alexander Ramsey.

Records of Governor Alexander Ramsey, 1860–1863

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/gov016.xml

Description: Accounting records, records concerning both civil and military appointments, letters received, records relating to pardons and other criminal matters, and petitions.

Henrik Shipstead papers, 1913–1953

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence, speeches, scrapbooks, clippings, news releases, printed items, and related materials concerning Shipstead's career as US senator from Minnesota, first as a member of the Farmer-Labor party and then as a Republican.

Henry H. Sibley papers, 1815–1932

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00595.xml

Description: Correspondence, financial records, legal papers, speeches, research note cards, and miscellany of Sibley, an early Minnesota fur trader, entrepreneur, and governor.

Harold Stassen papers, 1910s–1999

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00202.xml

Description: Papers documenting the life and career of a former Minnesota governor, presidential contender, naval officer, United Nations charter delegate, and Eisenhower cabinet member.

Rosalie Wahl papers, 1958–1998

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00430.xml

Description: Personal papers from the judicial chambers of Rosalie Wahl, first woman appointed (1977) and successively elected (1978, 1984, 1990) to the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Paul David Wellstone campaign records, 1962–2002

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/01138.xml

Description: Issue files, news clippings, audio and video cassettes, photographs, and other campaign records of three election campaigns waged by Wellstone, a progressive Democrat who represented Minnesota in the US Senate from 1991 to 2002.

Secondary

Adams, John S., and Barbara J. VanDrasek. Minneapolis-St. Paul: People, Places and Public Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Andersen, Elmer L. A Man’s Reach: The Autobiography of Elmer L. Andersen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Davis, W. Harry. Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2003.

Esbjornson, Robert. A Christian in Politics: Luther W. Youngdahl. Minneapolis: T. S. Denison, 1955.

Fraser, Arvonne. She’s No Lady. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2007.

Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Johnson, Cecil M. Minnesota’s Ole O. Sageng, 1871‒1963. Fergus Falls, MN: Otter Tail County Historical Society, 2015.

Latz, Robert (Bob). Jews in Minnesota Politics: The Inside Stories. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2007.

Mayer, George H. The Political Career of Floyd B. Olson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951.

Millikan, William. A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903‒1947. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

Sturdevant, Lori, with George S. Pillsbury. The Pillsburys of Minnesota. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2011.

Swain, Thomas H., with Lori Sturdevant. Citizen Swain: Tales of a Minnesota Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Wingerd, Mary Lethert. Claiming the City: Politics, Faith and the Power of Place in St. Paul. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Web

Governor of Minnesota.

https://mn.gov/governor

Minnesota State Legislature.

https://www.leg.state.mn.us

Minnesota Supreme Court.

http://www.mncourts.gov/SupremeCourt.aspx

.jpg?width=200&height=200&name=Ilhan_Omar%2C_official_portrait%2C_116th_Congress_(square).jpg)